Behind the Campaign Curtain

By Hailey Stangebye

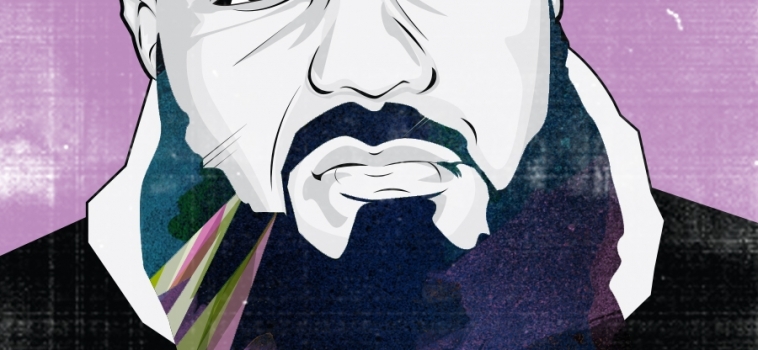

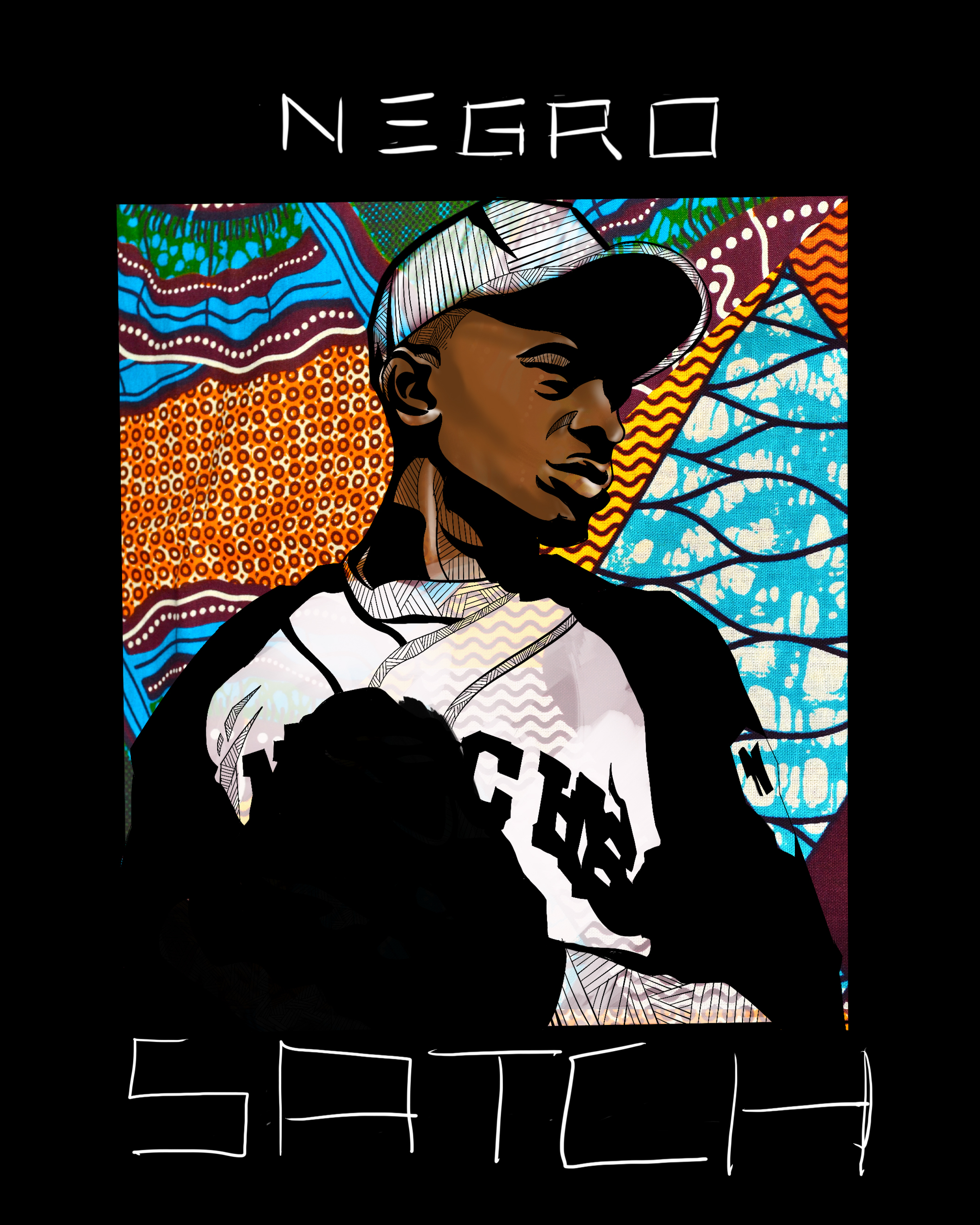

Photos courtesy of Marshall Shorts

Marshall Shorts is among the Columbus movers and shakers.

He likens this city to an open canvas — it’s a place where dedicated individuals can create tangible impacts on the community.

“Part of me feels like I can add a stroke on that canvas and become a part of building this city,” Marshall says. “Other cities might have more opportunity or, in some cases, more resources and people, but I think Columbus is exciting because it doesn’t always have that. You can get next to people and connect with people a lot easier. That’s unique.”

“Part of me feels like I can add a stroke on that canvas and become a part of building this city. Other cities might have more opportunity or, in some cases, more resources and people, but I think Columbus is exciting because it doesn’t always have that. You can get next to people and connect with people a lot easier. That’s unique.”

Marshall is a branding creative and one of the masterminds behind Creative Control Fest, but he’s also a local artist who has dedicated countless hours to help develop the Harlem Renaissance campaign in Columbus. He even designed the Harlem Renaissance logo.

“It’s not so much the acknowledgement or the celebration of the Harlem Renaissance. I think that part tends to get romanticized. But I think, more than anything, it provides an opportunity to educate and create a platform to have a real talk about what was successful about the Harlem Renaissance and what wasn’t so successful, so that we don’t repeat the same mistakes,” Marshall says. “Where are we 100 years later? Are we still facing some of the challenges that black folk had during that time period? Are artists still facing the same challenges 100 years later?”

“Where are we 100 years later? Are we still facing some of the challenges that black folk had during that time period? Are artists still facing the same challenges 100 years later?“

According to Marshall, the campaign in Columbus parallels the historical Harlem Renaissance in more ways than one.

On one hand, there’s been more positive exposure for black artists that have done and continue to do phenomenal work in their communities.

“The works created during the Harlem Renaissance were also in reaction to one of the most violent and tumultuous times against black folk in this country — across the country. While we recognize the art that was created and we celebrate that, that art came from a place of struggle and a place of discrimination and racism and violence and a lot of things.

“I think, for us today, when we see Black Lives Matter and other social movements, the response that happens as a result through art has parallels. Black Lives Matter is in response to vigilante and state violence, amongst other things,” Marshall says.

“The works created during the Harlem Renaissance were also in reaction to one of the most violent and tumultuous times against black folk in this country — across the country. While we recognize the art that was created and we celebrate that, that art came from a place of struggle and a place of discrimination and racism and violence and a lot of things.”

While the reality of this day and age can be disheartening, Marshall remains hopeful and says that he’s already begun to see some of the impacts of the campaign. The Harlem Renaissance Experience at the August Gallery Hop is an example of that.

“On the local level, I’m hoping that black artists feel empowered and that they have a platform to keep creating,” Marshall says. “I know there has been a conversation in Columbus for a long time around access to galleries and buyers and things like that in the Short North.”

This most recent hop opened doors for local, African American artists through galleries. It also added another physical layer to the Short North through the Temporary Mural Series — one, of which, was created by Marshall.

The momentum is here.

“My biggest concern is that, when this campaign ends, that it just ends,” Marshall says. “I want it to be sustainable. I want it to last beyond just the Harlem Renaissance campaign. I want this to be a part of the fabric of this city.”

Marshall says that this kind of organic, intentional sustainability is possible. But it often comes down to a dedicated few. As he mentioned before, Columbus is a place where individual effort counts.

“If you haven’t been involved in the campaign, make something,” Marshall says. “Get involved in some kind of way. If not with the Harlem Renaissance campaign, do something or create something or connect with folks. Continue to build this community outside of the campaign.”

“If you haven’t been involved in the campaign, make something. Get involved in some kind of way. If not with the Harlem Renaissance campaign, do something or create something or connect with folks. Continue to build this community outside of the campaign.“